📖 Fundamentals of optimization#

⏱ | words

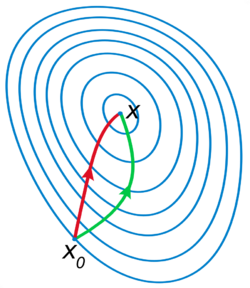

The goal is Weierstrass extreme value theorem which establishes the existence of max and min for continuous functions over compact sets

Talk about sets in \(\mathbb{R}\) first \(\rightarrow\) then transitions to functions

In the introductory lecture we have seen a few simple examples of optimization problems:

a solution exists

the solution is unique and not hard to find

However, for the majority of problems such properties aren’t guaranteed

We need some idea of how to check whether a solution to an optimization problems even exists!

Consider the problem of finding the “maximum” or “minimum” of a function

A first issue is that such values might not be well defined

Recall that the set of maximizers/minimizers can be

empty

a singleton (contains one element)

infinite (contains infinitely many elements)

Show code cell content

from myst_nb import glue

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

def subplots():

"Custom subplots with axes through the origin"

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

# Set the axes through the origin

for spine in ['left', 'bottom']:

ax.spines[spine].set_position('zero')

for spine in ['right', 'top']:

ax.spines[spine].set_color('none')

return fig, ax

xmin, xmax = 0, 1

xgrid1 = np.linspace(xmin, xmax, 100)

xgrid2 = np.linspace(xmax, 2, 10)

fig, ax = subplots()

ax.set_ylim(0, 1.1)

ax.set_xlim(-0.0, 2)

func_string = r'$f(x) = x^2$ if $x < 1$ else $f(x) = 0.5$'

ax.plot(xgrid1, xgrid1**2, 'b-', lw=3, label=func_string)

ax.plot(xgrid2, -0.25 * xgrid2 + 0.5, 'b-', lw=3)

ax.plot(xgrid1[-1], xgrid1[-1]**2, marker='o', markerfacecolor='white', markeredgewidth=2, markersize=6, color='b')

ax.plot(xgrid2[0], -0.25 * xgrid2[0] + 0.5, marker='.', markerfacecolor='b', markeredgewidth=2, markersize=10, color='b')

glue("fig_none", fig, display=False)

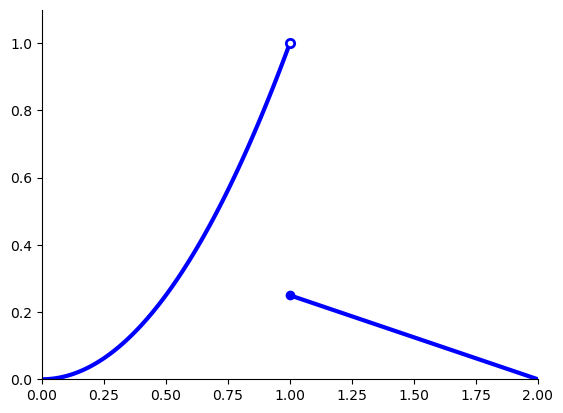

Example: no maximizers

The following function has no maximizers on \([0, 2]\)

Fig. 39 No maximizer on \([0, 2]\)#

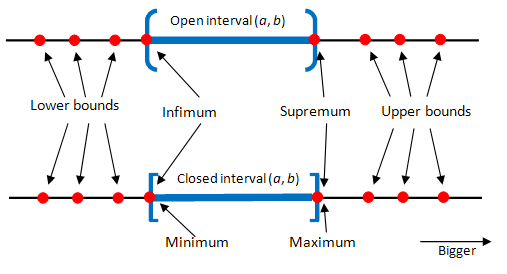

Suprema and Infima (\(\mathrm{sup}\) + \(\mathrm{inf}\))#

Always well defined

Agree with max and min when the latter exist

Definition

Let \(A \subset \mathbb{R}\) (we restrict attention to subsets of real line for now)

A number \(u \in \mathbb{R}\) is called an upper bound of \(A\) if

Example

If \(A = (0, 1)\) then 10 is an upper bound of \(A\) — indeed, every element of \((0, 1)\) is \(\leqslant 10\)

If \(A = (0, 1)\) then 1 is an upper bound of \(A\) — indeed, every element of \((0, 1)\) is \(\leqslant 1\)

If \(A = (0, 1)\) then \(0.75\) is not an upper bound of \(A\)

Definition

Let \(U(A)\) denote set of all upper bounds of \(A\).

A set \(A \subset \mathbb{R}\) is called bounded above if \(U(A)\) is not empty

Examples

If \(A = [0, 1]\), then \(U(A) = [1, \infty)\)

If \(A = (0, 1)\), then \(U(A) = [1, \infty)\)

If \(A = (0, 1) \cup (2, 3)\), then \(U(A) = [3, \infty)\)

If \(A = \mathbb{N}\), then \(U(A) = \varnothing\)

Definition

The least upper bound \(s\) of \(A\) is called supremum of \(A\), denoted \(s=\sup A\), i.e.

Example

If \(A = (0, 1]\), then \(U(A) = [1, \infty)\), so \(\sup A = 1\)

If \(A = (0, 1)\), then \(U(A) = [1, \infty)\), so \(\sup A = 1\)

Fig. 40 Upper and lower bounds, supremum and infimum of an interval on \(\mathbb{R}\)#

Definition

A lower bound of \(A \subset \mathbb{R}\) is any \(\ell \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(\ell \leqslant a\) for all \(a \in A\).

Let \(L(A)\) denote set of all lower bounds of \(A\).

A set \(A \subset \mathbb{R}\) is called bounded below if \(L(A)\) is not empty.

The highest of the lower bounds \(p\) is called the infimum of \(A\), denoted \(p=\inf A\), i.e.

Example

If \(A = [0, 1]\), then \(\inf A = 0\)

If \(A = (0, 1)\), then \(\inf A = 0\)

Some useful facts#

Fact

Boundedness of a subset of the set of real numbers is equivalent to it being bounded above and below.

Proof

The proof follows trivially from the definitions

Fact

Every nonempty subset of \(\mathbb{R}\) bounded above has a supremum in \(\mathbb{R}\)

Every nonempty subset of \(\mathbb{R}\) bounded below has an infimum in \(\mathbb{R}\)

Proof

Similar to the proof that all Cauchy sequences converge, follows from the density property of \(\mathbb{R}\)

Some textbooks allow all sets to have a supremum and infimum, even if they are not bounded. This is achieved by extending the set of real numbers with \(\{-\infty,\infty\}\)

Then, if \(A\) is unbounded above then \(\sup A = \infty\), and if \(A\) is unbounded below then \(\inf A = -\infty\).

Note

Aside: Conventions for dealing with symbols “\(\infty\)’’ and “\(-\infty\)” If \(a \in \mathbb{R}\), then

\(a + \infty = \infty\)

\(a - \infty = -\infty\)

\(a \times \infty = \infty\) if \(a \ne 0\), \(0 \times \infty = 0\)

\(-\infty < a < \infty\)

\(\infty + \infty = \infty\)

\(-\infty - \infty = -\infty\) But \(\infty - \infty\) is not defined

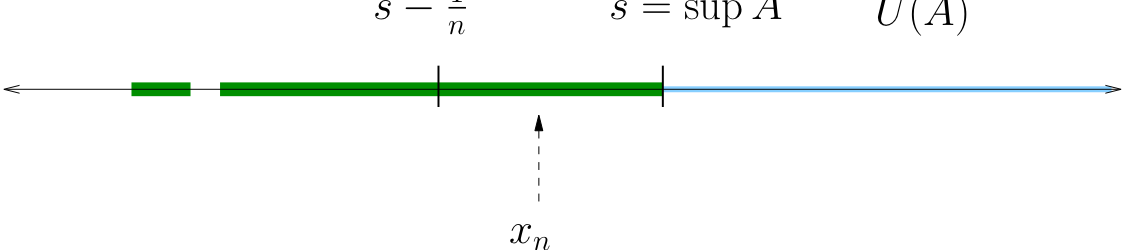

Fact

Let \(A\) be any set bounded above and let \(s = \sup A\). There exists a sequence \(\{x_n\}\) in \(A\) with \(x_n \to s\).

Analogously, if \(A\) is bounded below and \(p = \inf A\), then there exists a sequence \(\{x_n\}\) in \(A\) with \(x_n \to p\).

Proof

Note that

(Otherwise \(s\) is not a sup, because \(s-\frac{1}{n}\) is a smaller upper bound)

The sequence \(\{x_n\}\) lies in \(A\) and converges to \(s\).

The proof for the infimum is analogous.

Maxima and Minima (\(\max\) + \(\min\))#

Definition

We call \(a^*\) the maximum of \(A \subset \mathbb{R}\), denoted \(a^* = \max A\), if

We call \(a^*\) the minimum of \(A \subset \mathbb{R}\) and write \(a^* = \min A\) if

Example

For \(A = [0, 1]\) \(\max A = 1\) and \(\min A = 0\)

Relationship between max/min and sup/inf#

Fact

Let \(A\) be any subset of \(\mathbb{R}\)

If \(\sup A \in A\), then \(\max A\) exists and \(\max A = \sup A\)

If \(\inf A \in A\), then \(\min A\) exists and \(\min A = \inf A\)

In other words, when max and min exist they agree with sup and inf

Proof

Proof of case 1: Let \(a^* = \sup A\) and suppose \(a^* \in A\)

We want to show that \(\max A = a^*\)

Since \(a^* \in A\), we need only show that \(a \leqslant a^*\) for all \(a \in A\)

This follows from \(a^* = \sup A\), which implies \(a^* \in U(A)\)

Fact

If \(F \subset \mathbb{R}\) is a closed and bounded, then \(\max F\) and \(\min F\) both exist

Proof

Proof for the max case:

Since \(F\) is bounded,

\(\sup F\) exists

\(\exists\) a sequence \(\{x_n\} \subset F\) with \(x_n \to \sup F\)

Since \(F\) is closed, this implies that \(\sup F \in F\)

Hence \(\max F\) exists and \(\max F = \sup F\)

Segway to functions#

Of course, in optimization we are mainly interested in maximizing and minimizing functions

Will apply the notions of supremum and infimum, minimum and maximum to the range of a function

Equivalently, we may consider the image of a set \(X \subset \mathbb{R}^N\) under a function \(f\)

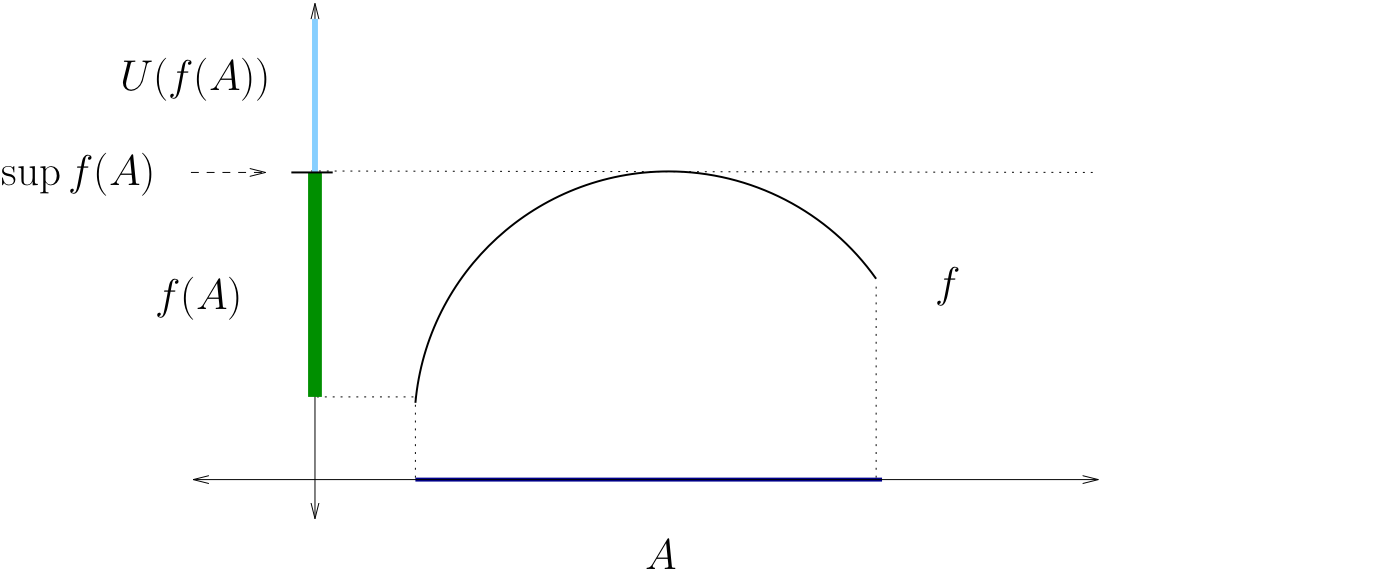

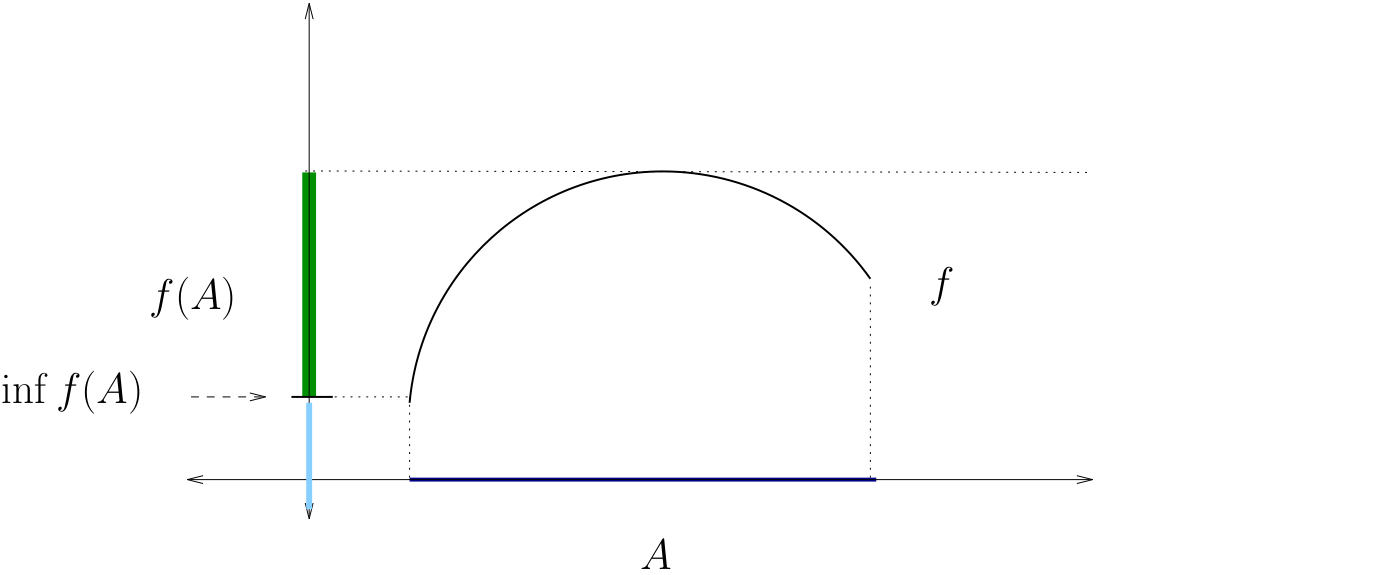

Definition

Let \(f \colon A \to \mathbb{R}\), where \(A\) is any set

The supremum of \(f\) on \(A\) is defined as

The infimum of \(f\) on \(A\) is defined as

Fig. 41 The supremum of \(f\) on \(A\)#

Fig. 42 The infimum of \(f\) on \(A\)#

Definition

Let \(f \colon A \to \mathbb{R}\) where \(A\) is any set

The maximum of \(f\) on \(A\) is defined as

The minimum of \(f\) on \(A\) is defined as

$$

Definition

A maximizer of \(f\) on \(A\) is a point \(a^* \in A\) such that

The set of all maximizers is typically denoted by

Definition

A minimizer of \(f\) on \(A\) is a point \(a^* \in A\) such that

The set of all minimizers is typically denoted by

Weierstrass extreme value theorem#

Fundamental result on existence of maxima and minima of functions!

Fact (Weierstrass extreme value theorem)

If \(f: A \subset \mathbb{R}^N \to \mathbb{R}\)

is continuous and \(A\) is closed and bounded,

then \(f\) has both a maximizer and a minimizer on \(A\).

Proof

Sketch of the proof:

If \(f\) is continuous and \(A\) is compact, then \(f(A)\) is bounded, see relevant fact

Because \(f(A)\) is bounded \(\sup f(A)\) and \(\inf f(A)\) exist, see relevant fact

There is a sequence \(\{y_n\} \in f(A)\) converging to sup/inf, see relevant fact

Consider the corresponding sequence of \(x\) such that \(y=f(x)\)

It may not be convergent, but is bounded (belongs to compact), therefore contains a convergent subsequence (by Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem), see relevant fact

Let \(c\) be the limit of a convergent subsequence

Then by definition of continuity \(f(c)\) is the limit of the sequence \(f(x_n)\)

\(f(c)\) must then be the same as the limit of the sequence \(y_n\) = sup/inf due to the fact that any sequence can have at most one limit, see relevant fact

Therefore sup/inf is attained at \(x=c\)

Example

Consider the problem

where

\(r=\) interest rate, \(w=\) wealth, \(\beta=\) discount factor

all parameters \(> 0\)

Let \(B\) be all \((c_1, c_2)\) satisfying the constraint

Exercise: Show that the budget set \(B\) is a closed, bounded subset of \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

Exercise: Show that \(U\) is continuous on \(B\)

We conclude that a maximizer exists

References and further reading#

References

Simon & Blume: 12.2, 12.3, 12.4, 12.5, 13.4, 29.2, 30.1

Sundaram: 1.2.6, 1.2.7, 1.2.8, 1.2.9, 1.2.10, 1.4.1, section 3